Deej-A.I. App

A couple of years ago I created a deep learning model to automatically generate playlists, which I deployed as a webpage using Flask, PHP and JavaScript and as a simple WebView app on iOS and Android. I decided to put into practice what I have learned about web programming and deployment since then and rewrite the whole thing as a responsive ReactJS / React Native application served on a Kubernetes cluster.

The previous incarnation of the website (the code for which can be found here) took the idea of a SPA (Single Page Application) a little too literally and was a huge single file of HTML, CSS, JavaScript and PHP. React turned out to be a great framework which would oblige me to make the code more modular and at the same time make it easier to add new functionality, such as the ability to rate and browse playlists created by other people.

I had taken a shortcut to be able to publish my app on the Google Play Store and Apple App Store by using a WebView: the application was basically nothing more than a browser set to point at my website. To make the app more responsive and have more of an iOS / Android feel, I used React Native and Expo to create native versions of the web application. This wasn’t as straightforward as I was expecting it to be, especially as I only had the idea to do this once I had already developed the ReactJS version. To begin with, React Native doesn’t support the standard HTML tags like <h1> or <a>. I refactored the code to have as large a common codebase as possible and created wrappers for the platform specific components. An alternative approach would have been to have separate projects for the ReactJS and React Native applications, and move all the common code into a separate NodeJS module.

I also wanted to automate the deployment of the server and allow for it to auto-scale, just in case my application became an overnight sensation ;-). The first step was to write a Dockerfile for the backend FastAPI server. I then made a Helm chart which can be used to install the application - the backend server, a MySQL database to store the playlists and a Redis instance to cache server-side requests - on anything from your Desktop PC to a public cloud like AWS. By tweaking a few parameters you can control the size and number of instances as well as the autoscaling rules. If necessary, the databases can be easily replicated to ensure high availability. It can also be configured to automatically provision a SSL certificate for HTTPS connections using Let’s Encrypt.

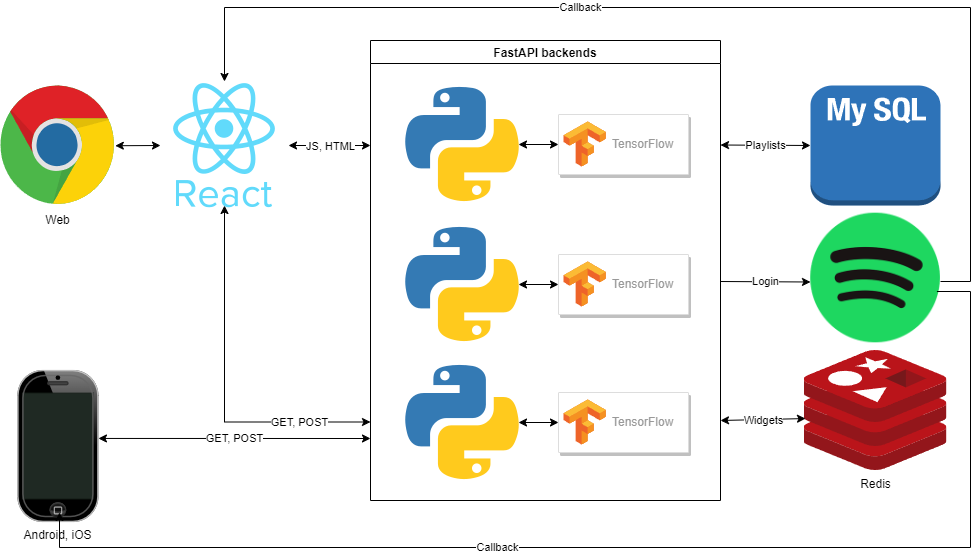

The backend FastAPI sever actually has several responsibilities. First and foremost, it handles the calls to the underlying deep learning Tensorflow models. It also serves the frontend JavaScript and HTML as well as storing and retrieving playlists from the database. Lastly, it takes care of the Spotify API authentication flow (slightly simplified in the diagram below). The Spotify API is called from the backend to be able to create user playlists and, for this, it is important that the API credentials are not exposed to the client. The frontend also calls the Spotify API directly in order to find out what track the user is currently playing in order to be able to search for similar sounding songs. For this level of authentication, only the client ID is required (as opposed to the client secret) and this can safely be handled in the frontend. The application also makes use of track and playlist widgets provided by Spotify. In order to be able to display a playlist widget for a playlist that has not been uploaded to Spotify, I wrote a function which creates a custom playlist widget on the fly by injecting the appropriate HTML using BeautifulSoup. In theory, it would be possible to allow users to play the tracks in their entirety if I were to authenticate with my Spotify user account on the server. This, however, would be in breach of the Spotify Developer Terms of Service. As these widgets are requested frequently, they are cached server-side in a Redis data store. The web application uses service workers to cache and lazily refresh requests client-side.

I have tried to follow best practices by including automated unit tests with Jest and Pytest which are run on GitHub Actions every time I push to the main branch or a pull request is merged. In fact, as the number of minutes of compute time for GitHub Actions is limited in the free tier, I have a hook that runs the tests locally whenever I do a commit.

Overall, my experience has been very positive. React was a joy to work with and the hot reload feature meant I could iterate very quickly in development. This was even more of a factor with the mobile app development, for which Expo completely avoided the painfully slow compile and install times of Android Studio and XCode. I am a little bit in two minds about PWAs (Progressive Web Applications). The service workers seem to cache too aggressively and I worry that there are will be users running old versions of the frontend that will eventually break, that not even a hard refresh on the browser will necessarily remedy. Working with Kubernetes was more of a love-hate affair. When it works it works everywhere, but getting those fiddly YAML configuration files right requires a lot of digging around on the internet. I do love the fact that I can deploy the whole stack with just one command. I don’t even need to worry about SSL certificates any more!

Tech stack

Robert Dargavel Smith

Robert Dargavel Smith